Mesopotamian Architecture

Mesopotamian architecture, emerging from the fertile lands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, represents one of the earliest and most influential architectural traditions in human history. As the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia gave rise to some of the first urban centers, monumental structures, and complex societies. The architecture of Mesopotamia, spanning thousands of years and various cultures—including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians—reflects not only their innovative construction techniques but also their religious, political, and social values.

Historical and Cultural Context

Mesopotamian architecture developed in a region that is often referred to as the “Land Between the Rivers,” encompassing modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and parts of Syria and Turkey. This area saw the rise of the world’s first cities, states, and empires, with Uruk, Ur, Babylon, and Nineveh among the most famous. The architectural achievements of these societies were closely linked to the needs of urbanization, administration, and religious practice.

As one of the first regions to develop written language, advanced agriculture, and centralized governance, Mesopotamia’s architecture also reflects the complexity of its social structures. Temples, palaces, and ziggurats were built to house gods, rulers, and bureaucrats, while city walls, canals, and gates protected and sustained burgeoning urban populations.

Materials and Construction Techniques

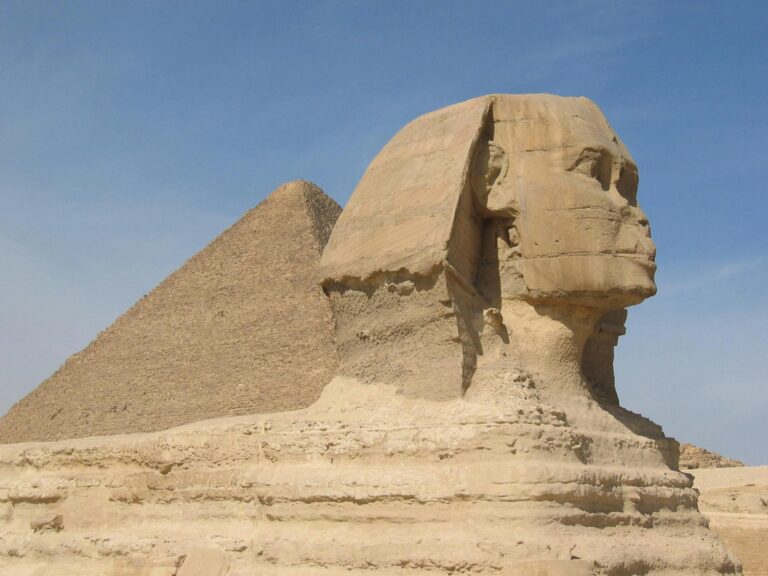

Unlike Egypt, Mesopotamia lacked abundant stone resources, which heavily influenced its architecture. The primary building material used was mudbrick, made from the clay-rich soil of the region. These bricks were dried in the sun or fired in kilns to increase their durability. While mudbrick was plentiful and easy to produce, it was also vulnerable to erosion from rain and time, leading to the frequent need for repairs and reconstructions.

In areas where stone was more accessible, such as in northern Mesopotamia, stone was used sparingly for foundations or decorative elements. Bitumen, a natural asphalt, was also commonly used as a mortar or waterproofing agent, particularly for the construction of city walls and canals.

Despite the limitations of their building materials, Mesopotamian architects developed sophisticated construction techniques. The use of recessed and projecting walls, for example, gave structures a sense of rhythm and dynamism, breaking the monotony of large brick surfaces. They also developed complex vaulting and doming techniques to cover larger interior spaces, particularly in monumental buildings.

Types of Structures

Ziggurats

Perhaps the most iconic structure of Mesopotamian architecture is the ziggurat, a massive terraced platform that served as a religious temple. Ziggurats were constructed as the physical and spiritual link between the heavens and the earth, embodying the Mesopotamians’ belief in the divine authority of their gods. These structures were dedicated to the gods and housed their shrines at the summit.

The Ziggurat of Ur, built in the early 21st century BCE, is one of the best-preserved examples. This massive structure, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, was constructed with three terraces and a large staircase leading to the top. The towering height of ziggurats symbolized the importance of the gods, and only priests or royalty were allowed access to the uppermost shrine. Ziggurats, unlike Egyptian pyramids, were solid structures made of mudbrick with no internal chambers.

Temples

Temples were the heart of Mesopotamian cities and played a central role in both religious and civic life. Unlike the vast interior spaces of later Greco-Roman temples, Mesopotamian temples were typically more closed and introspective, emphasizing the separation between the divine and the mundane.

Many of these temples were built in a tripartite design, with a central hall flanked by smaller side rooms. The central hall often housed the statue of the god to whom the temple was dedicated. The exterior of the temples was often decorated with cone mosaics, colored and embedded into the mudbrick to form geometric patterns and protect the walls from weathering.

The White Temple of Uruk (circa 3500 BCE) is a prime example of early Sumerian temple architecture. Perched atop a ziggurat-like platform, this temple was built to honor Anu, the sky god. Its walls were brightened with whitewashed plaster, a striking contrast to the surrounding desert.

Palaces

Palaces were grand architectural expressions of royal power and the administrative heart of Mesopotamian cities. These structures were larger and more elaborate than temples, often containing multiple courtyards, gardens, halls, and storage rooms. Palaces were not just homes for the kings; they were also centers of political activity, housing officials, scribes, and soldiers.

The Palace of Sargon II at Dur-Sharrukin (modern-day Khorsabad) is an excellent example of Assyrian palace architecture. Built in the 8th century BCE, this massive complex was designed to symbolize the king’s divine authority. It featured elaborate gateways guarded by lamassu—colossal stone sculptures of winged bulls with human heads—intended to protect the palace and impress visitors.

Inside, the palace was decorated with elaborate bas-reliefs depicting the king’s military victories, religious ceremonies, and daily life. These intricate carvings offered a visual narrative of the ruler’s might and divine favor, reinforcing the idea that the king was chosen by the gods.

Urban Planning and City Walls

Mesopotamian cities were some of the earliest examples of organized urban planning. Cities like Ur and Babylon were laid out according to specific plans, with distinct residential, religious, and administrative districts. Streets were typically narrow and winding, with homes built close together, reflecting the high population density within city walls.

City walls were a crucial aspect of Mesopotamian urban planning, built not only for protection but also as a symbol of the city’s power and wealth. The walls of Babylon, under the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II (circa 6th century BCE), were some of the most famous in the ancient world. The Ishtar Gate, one of the eight gates leading into Babylon, was adorned with vivid blue-glazed bricks and reliefs of lions, dragons, and bulls, symbolizing the strength of the city’s gods.

Religious and Symbolic Influence

As in Ancient Egypt, religion played a central role in shaping Mesopotamian architecture. Temples and ziggurats were designed as focal points of religious activity and were constructed to reflect the divine order of the universe. The Mesopotamians believed that the gods resided in the heavens but interacted with the world through these sacred structures, thus the towering height of ziggurats symbolized humanity’s connection with the divine.

Furthermore, architecture was seen as a way to express cosmic order. Temples and cities were laid out with the cardinal points in mind, and religious structures often aligned with celestial events. The dedication of so much labor and resources to religious and royal buildings reflects the deep connection between architecture and theocratic governance, where the ruler was seen as both a political leader and a representative of the gods on earth.

Assyrian and Babylonian Architectural Advancements

As Mesopotamian civilization progressed, both the Assyrians and Babylonians made significant contributions to architectural innovation.

Assyrian Architecture

The Assyrians, particularly during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BCE), were known for their militaristic and grandiose architecture. Palaces such as those in Nineveh and Nimrud were fortified with massive walls and adorned with intricate carvings. The Assyrian reliefs, depicting scenes of hunting, warfare, and rituals, became a hallmark of their architecture.

Another key feature of Assyrian architecture was the use of large courtyards, often surrounded by colonnades, which served as central gathering spaces within palaces and temples. The courtyards created a sense of openness while maintaining the enclosed, inward focus characteristic of Mesopotamian design.

Babylonian Architecture

Babylonian architecture, particularly during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, reached new heights of sophistication and grandeur. The city of Babylon, with its famed Hanging Gardens, became a symbol of wealth and power. Although the existence of the Hanging Gardens remains a matter of debate among historians, Babylon’s real architectural achievement was the Etemenanki, a massive ziggurat believed to have inspired the biblical Tower of Babel.

Babylonian architecture was also renowned for its use of glazed brickwork. The Ishtar Gate, a striking example of this technique, showcased blue-glazed bricks adorned with reliefs of animals representing the gods Marduk, Adad, and Ishtar. This vibrant architectural decoration was a significant departure from the more austere styles of earlier periods.

Legacy and Influence on Later Civilizations

The architectural innovations of Mesopotamia laid the foundation for many later civilizations. The use of mudbrick, the development of monumental public spaces, and the integration of religious symbolism into architecture influenced the architectural traditions of the Persians, Greeks, and Romans.

Persian architecture, particularly the grand palaces of Persepolis, borrowed heavily from Mesopotamian design elements, such as columned halls and decorative reliefs. Greek architecture also absorbed elements of Mesopotamian urban planning and temple design, which later influenced Roman architecture.